GQ AWARD: INNOVATION. A DECADE OF FUTUREFLEX

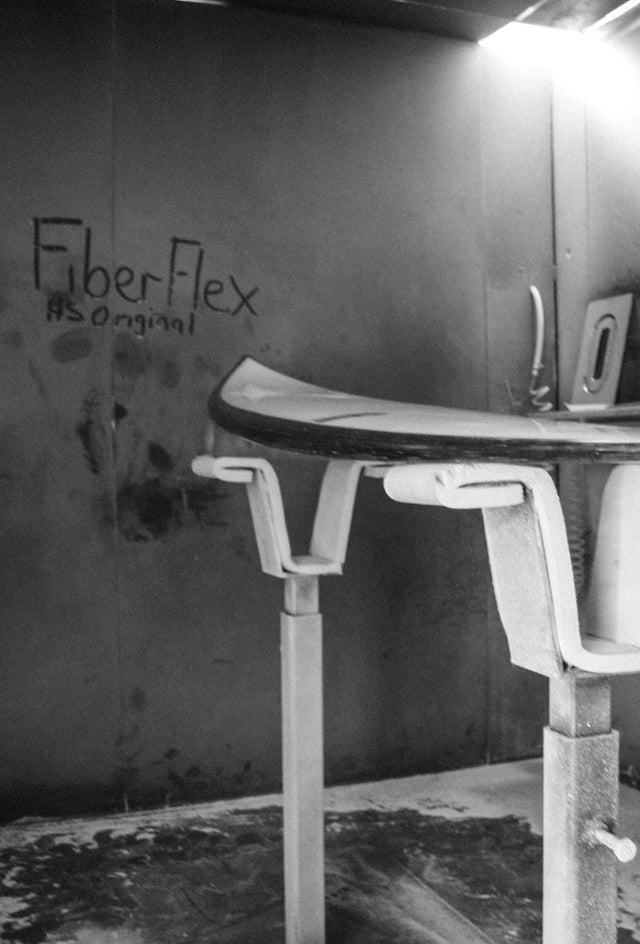

Image: An early FF board, captured in Hayden’s Mona Vale shaping bay in 2007.

This year marks two significant milestones for Hayden and the brand – Haydenshapes turns 20 and FutureFlex turns 10. This year (on November 15th) GQ Magazine Australia awarded Hayden for “Innovation” at the 2017 MOTY event held at The Star, Sydney. A huge thank you to Mike Christensen and Nick Smith at GQ for pulling together the awards and a fun event, Audi, Patron (for the wild hangover) and to Prada who had Hayden suited up and looking sharp.

Other winners on the night included designer Virgil Abloh of OFF–White, boxer Jeff Horn, Viking’s legend and Aussie actor Travis Fimmel, Actor Jeff Goldblum screenwriter (Lion) Luke Davis and muso Flume among others. Read more and check out Hayden’s speech here.

Amongst a haze of tequila, we snapped a few shots on the Galaxy S8, stole a couple extras from google (studio shots by @sonnyphotos) and got Hayden to scribe some commentary below.

It’s not everyday that surfboard manufacturing is recognised or perhaps even talked about outside of core surf so to acknowledge this cool award and celebrate a decade of our signature and original tech launching to market, we thought we’d post a chapter excerpt from Hayden’s book New Wave Vision. It’s a longread, that goes back to the days when FutureFlex (formerly FiberFlex) was conceived.

NB- You can purchase NWV in it’s entirety via our online store and in book shops Australia wide.

******

CHAPTER EXCERPT: IDEAS AND INNOVATION.

The Birth of FutureFlex.

The chain reaction was set off when I met Tom Carroll, the former two-time world surfing champion, at Queenscliff beach in Manly.

Tom’s brother Nick, also a former professional surfer, was one of the most respected journalists in the surf world. Like Tom, Nick had retained his keenness and was extremely articulate about surfing and surfboards. Nick and Tom were the sons of Vic Carroll, a former editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, and they could communicate in such a way that not only made sense of things, but infected you with their enthusiasm.

Nick did me a favour early in my shaping career. He was a judge for the Australian Surfing Life magazine annual board guide, where a group of half a dozen experienced surfers take boards from about 25 shapers and ride them for a few days before publishing a review. When I first put a board into the ASL test, Nick rode it. The shape of the board was clean and the rockers resembled some of the boards Nick had ridden back in the early ‘90s, but the fins were too far back, more in line with what I was shaping for Craig and myself. Nick reviewed the board and wouldn’t let anyone else ride it, in case they cooked me. He still gave it an honest review, but he wasn’t anywhere near as harsh as he could have been. Later, he gave me constructive feedback and I re-made the same board with the fin placement adjusted. Nick told me it was one of his favourite boards to date.

A year later, I was in the ASL guide again, and Nick invited me to attend their test up at Yamba on the New South Wales north coast. Four surfers, all of different sizes and weights, were allocated six boards each. The tests would go over a five-day period, and the boards would be ridden in different conditions. I wasn’t one of the featured surfers, but my boards were part of the line up. It was a fun process and for me a great opportunity to learn about other designers and their boards. I was able to ride loads of different designs, coming to terms with how they felt under my feet, seeing how they all worked and learning what I could.

While driving back, we got talking about materials. I said to Nick, ‘I’ve been dabbling in carbon fibre and testing out some parabolic carbon stringers. Surely I can build a board with a parabolic frame, not stringers, but like a tennis racquet frame, using carbon fibre.’

My thought was that a carbon fibre frame would offer an enlarged ‘sweet spot’ and a lot of spring out of the middle. Instead of the board twisting around the central stringer, the carbon fibre frame would stiffen up the rail line, giving the board more speed and drive. A traditional wooden stringer in a surfboard could only take so much flexing and returning before it lost its memory of elasticity and liveliness. A carbon-fibre frame could keep those properties indefinitely.

‘I’m going to build one!’ I said.

Nick said, ‘Yeah, do that!’ He probably thought, This’ll be interesting…

On the way home, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. When you think you’ve come up with an idea like that, you don’t sleep well. That week, I constantly woke throughout the night bursting with different ideas and concepts of the board and how I was going to build it. I had covered every stage of manufacturing, rewinding the process in my mind if I hit a roadblock, to find a new way to the finished product. It was already real to me. Back at the factory, I got on the phone to suppliers of EPS foam, carbon fibre and other material manufacturers. All I knew about some of these companies was what I’d picked up by looking up on the internet who supplied these products to the aerospace and yachting industries. I needed to create a prototype and I was not patient about it.

I tracked down all of the materials – carbon fibres, epoxy resin, high density foam, EPS foam and a vacuum pump – and began building the board.

That first parabolic carbon fibre frame board, which I still have, came out of a similar method of manufacturing as other vacuum-bagged constructions. I made the carbon fibre into a square C-section – imagine a capital ‘I’ cut vertically down the centre, following the rail of the EPS core. This was a concept from structural engineering, and although I was only using half the I beam, it would be efficient in supporting the flex of the surfboard. I placed the carbon fibre frame internally in the board around the EPS core and vacuum laminated the high-density foam on the deck, bottom and rails. I could intuit the theory. As you take off on a wave, instead of feeling the stiffness in the centre and the flex on the rail line, you would get the same stiffness in the centre, but your rail line would flex less. I was looking to speed up the flex response of the rail. Your rail is where your surfing and to improve it’s flex response would mean your board would have more speed.

When it came to naming my technology, parabolic carbon fibre frames and unique flex patterns were a mouthful. I needed a quick solution or else people might be turned off by the apparent complexity. I had created a prototype and now I needed a name. Bouncing ideas with a friend, I wanted a name that spelt out what the product was, a carbon fiber frame that flexed. ‘FiberFlex’ was what we came up with, as it felt professional and neutral enough to potentially suit the tastes of all types of shapers I wanted to get using the technology. The logo came next: a monochromatic pair of parallel lines bending to represent two f’s for Fiber and Flex. Simple but stylish. Next step was filing trademarks and obtaining registration. (…. FYI… It turned out FiberFlex could not be trademarked in Europe. Thus, after around 4 years after launch in Australia and as we began to go international, it was renamed to FutureFlex.)

Over the next four to six months, my initial plan was to market and sell the technology in boards that only I could make, selling for $1295, a significantly higher retail price than most surfboards. But it would be evident where the extra costs came in and, I hoped, where the extra value was for surfers. There were so many tweaks to normal production, it really was like creating a completely new piece of surfing equipment. For example, I began working with vacuum-bagged laminations, an idea used in the construction of boat hulls out of composite parts, which sucked all the pieces together and held them down.

Craig, Marti and other surfers rode these boards on trips, we did shoots and got them into magazines. We were selling direct to consumers rather than through retail. I got about 30 orders straight up, within the first week. We began manufacturing, but were hitting roadblock after roadblock. The technical difficulties were becoming so hard that I couldn’t see us scaling it up. This set me thinking about revamping the actual design.

I still had faith in the concept, but I didn’t have the simplest method of manufacturing it. I stripped out elements including the technicality and cost of our process and materials, and was guided by what might be customisable. A major change during the next period was in the construction of the carbon frame itself. In the earlier prototypes, it was placed internally around the lightweight EPS core. From an engineering point of view, the vertically halved I-beam was extremely strong. But it was messy to vacuum laminate and glue the rails to the outside of the carbon frame & then re-CNC cut the shape of the board. It took so much time that I couldn’t figure out how to do it efficiently myself. Nor could I see how this problem would fit the vision I had of licensing it out as a technology that other shapers could use. The process itself had to be easier. If I was the only person who could manufacture FiberFlex boards, then I would be back where I started. It had to be more easily replicable.

I went back to the drawing board. We had something like a 20-step manufacturing process that was fiendishly hard to train staff to do. I thought, The big lesson I learnt in high school tech classes was KISS – Keep It Simple, Stupid. Why am I not applying that now? The carbon fibre only had to be on the rail of the board; it didn’t need to be exactly the same as a parabolic wooden stringer. What if I attached the carbon fibre as a tape around the rail? You could then see it, which was better than hiding it from both an aesthetic and practical point of view, and you could apply it to any shape.

The original carbon fibre wouldn’t have contoured that way, so I worked with the company supplying it to develop a carbon fiber tape that could fit around the shape exactly as we wanted. A few secrets in that process enabled us to lay it on by hand.

This revolutionised the process and the FiberFlex surfboard itself. The weight of carbon in the frame went down from 200 to 120 grams when it became tape.

Also, changing from an internal carbon frame to a tape would empower me to achieve my ‘Dolby Digital’ dream. The design brief had to be flexible enough to use on any shaper’s board. I wanted to be able to scale, manufacturing in any traditional surfboard factory’s facilities. The tape also improved the presentation to a point where I could take to the marketplace. It brought in a clean, black-and-white aesthetic, which began to be synonymous with the both the Haydenshapes and FiberFlex brand. The tape also followed the line of the old leopard-skin rail of my Terry Fitzgerald Hot Buttered surfboard, my pride and joy in childhood.

Fortunately, my suppliers opened their R&D departments to me. Once I was purchasing a lot of product from them, they wanted to develop ideas collaboratively and I wanted my materials to be custom and exclusive to my technology. Doing this would also be another way to protect myself, as it would be one thing to replicate aesthetics, but another to copy the performance and feel, which are so influenced by the materials and how they flex. I had to adapt all along the way. For instance, I had been concerned by the slight ‘step’ on the board where the carbon went on, an unevenness between the layer of carbon tape and the board’s surface. To fill in that step, the lamination had to go through a second stage. Filler resin had to go in, and then you had to grind it back. That was an extra stage in manufacturing. We managed to get the carbon fibre woven differently, in such a way that it was no longer raised above the surrounds. That tiny change could improve our manufacturing efficiency immensely.

As soon as the first board came out of production, I met Tom Carroll down at Newport Beach. The waves were light onshore, about head-high. Tom got a couple of waves, and then gave me a turn. It didn’t feel that great to me – it was too rigid around the frame.

More than anyone in the world, Tom can gauge a board through riding it just once. He took the board back and paddled into a wave. Suddenly he got some electric speed out of his bottom turn, and jammed a big hack on the inside. Then the wave bottomed out. The board’s nose got buried in the sandbar. It buckled, and was done. But Tom was all excited.

‘Did you see that?’ he said. ‘I felt it! There was definitely something there.’

His feedback gave me enough encouragement to go back to my suppliers. That board was over-engineered, with an imbalance between the over-stiffness of the frame and the lack of firmness in the foam. I had to bring those two factors together.

I said, ‘That carbon fibre was five times too stiff. What other materials have you got?’

They brought out a flat-sheeted carbon fibre, all the fibres flattening out in one direction, as thin as an A4 sheet of paper. In the factory, we got those longitudinal fibres to follow the rail line by hand. I built another board for Tom and one for myself. The carbon was messy and the boards didn’t look pretty, but appearance was not my concern yet.

Tom rode his new board at three-foot Bungan Beach, and felt something special again. I rode mine too, and while I didn’t have Tom’s skills I also felt the “thing”. There was enough bend in the board and even more acceleration, the bend responding back to you after a turn. The stiffer the board, the more it will embrace the wave’s power, but on smaller waves you need the flex response so you can accelerate. By dropping the grade of the carbon and increasing the flex, I’d been able to bring the product to life. It had now had a real spark.

Tom and I ran up the hill, excited as little kids, chattering away. I was thinking, I’ve got to patent this.

That night, I sat on my computer thinking about Simon Anderson and the thruster. It was the ultimate cautionary tale. Simon had invented the three-finned board, a combination of a single-fin and a twin-fin, in the early 1980s but had never taken out a patent. There’s all sorts of debate about what claim he really had and whether he would have been able to patent it, but by 2006 when I was developing FiberFlex, the whole world was riding thrusters and Simon had not made a cent out of them. Whether it was accurate or not, the story carried a clear lesson for any designer: If you think you’ve invented something, get a patent.

PROTECT YOUR IDEAS

Being original with an idea in this day and age is a difficult task. An important truth the creative world must swallow and accept is that more than one person can have the same idea. Yes, it is possible and it happens daily, which is why patents, trademarks and copyright exist. People on the internet and social media will not hesitate in making accusations and berating an individual or brand for ‘idea theft’ whether there is truth to it or not. Sometimes there is. It can be a lot harder or perhaps not even worth your while to go down the road of trademarking or protecting a more short term or ‘seasonal’ design like say, a t-shirt print. When it comes to an idea or concept that showcases an inventive step forward, you should protect your ideas and look to obtain patent protection. It can be costly, but well worth it to you in the long run.

My research showed me that there were two types of Australian patent. One was a very formal ‘standard patent’, requiring a lot of paperwork, legal advice and expense. Fortunately, there was another patent ‘lite’ for people like me, called an innovator’s patent. It only cost a hundred or so dollars, which was all my so-called R & D budget would allow at that time.

I filled out the online form for an innovator’s patent. You had to describe your invention in the simplest terms possible. I wrote one sentence: ‘A surfboard comprising a parabolic carbon fibre frame.’ That’s what it was, and that’s what I wrote. It proved to be the most important sentence I’ve ever written. Its simplicity and breadth was its strength.

A few days later, I got cold feet, thinking, It can’t be that easy, I must be missing something. Should I have got a standard patent?

One of the differences between the two was that you could apply a standard patent internationally as a design concept, whereas innovator’s patents were only valid in Australia. So I was vulnerable to someone doing what I’d done overseas. But on the other hand, innovator’s patents weren’t second-rate. A recent court case had given them the same weight as standard patents.

I was still nervous, however. When you think you’ve come up with a ground-breaking idea, you don’t sleep well. I’d met a guy at the beach, a backyard inventor, who had designed a chip technology for automatic car keys. We got talking about patents, and he recommended I make an appointment with Lee Pippard, a patent lawyer with the firm Spruson and Ferguson. Lee was a surfer from Cronulla and would at the very least have a sense of where I was coming from.

When we met, one of the first things Lee said was, ‘You’re bloody lucky that you wrote that vague sentence in your innovator’s patent. On the back of that, we can turn the innovator’s patent into a standard patent. But you have to do it before the innovator’s patent gets publicised, which is within two days.’

Lee then wrote the full 25-to-30-page document, and we filed international patents on the back of that.

When Lee wrote the patent, setting the story and explaining the invention, we described the performance and flex we were seeking by the use of carbon fibre. We had to show a full understanding of what we were doing from start to finish in formal legal language. It was a snap learning curve for me, as I had only built ten of these boards at the time and hadn’t even sold one.

What happens after you file a patent is that anyone who thinks you’re infringing on what they have done can lodge a ‘citing’ against it, as prior art. There were a few citings, made by the patent examiner, against me for windsurfing boards and sailboat keels and masts, from manufacturers who had used carbon fibre in water action sports. One ‘potential prior art’ citing mentioned the use of carbon fibre in surfboards, but it was purely for strengthening, as a secondary material across a large surface of the board, and it could have been numerous other materials. My design concept was specifically about using the carbon fibre in a parabolic rail-following pattern for flex not just using it broadly for strengthening a board.

I wondered what the patent would really do. Would it safeguard me against what had happened to Simon Anderson and his thruster design? If people wanted to copy the idea, would I be able to police them? Lee left me with some sage advice. ‘A patent,’ he said, ‘is like an insurance policy that you never want to claim on. Sometimes you might be required to police it, but it can be even more useful as an official stamp to show that you own an idea especially when entering into commercial arrangements with customers. It’s also there for the times when you do need to use it as a policing tool.’

He knew exactly where I was coming from. This was my Dolby Digital. I wanted to sell this technology to all shapers, and that’s what the patent had to show: that it was my technology to sell.

*

Having conceived the idea and filed a patent, was I going to able to manufacture the boards? As usual, I hadn’t thought about the obstacles. They might have stopped me from innovating in the first place.

In those early days, I became consumed by getting FiberFlex right. The carbon-fibre frame didn’t contribute really any more longitudinal stiffness to the board than a central wooden stringer – which contributes to about 45% of a board’s stiffness – but the distribution around the rail placed different demands on the foam, glass and resin.

The density of standard polyurethane foam was, and is, around 48 kilograms per cubic metre. EPS foam was a lot less dense – it reached 28 kilograms per cubic metre. For that reason, EPS had mainly been used as a foam core sandwiched between layers of higher-density foam on the top and bottom. I wanted something of a hybrid: an EPS foam that had the same density as polyurethane foam, lighter weight than a standard blank but also with the same compressional stability. Did such a thing even exist?

I worked on it with a local Sydney EPS foam manufacturer. We spent several weeks blowing the EPS foam, putting it in ovens, drying it out and cutting it up. We eventually got it up to 42 kilograms per cubic metre, but this was another cost. I worked with my epoxy supplier, my carbon fibre supplier, my resin supplier, over about two years until we got FiberFlex right.

The next step, and maybe the critical one, was to address preconceptions among surfers, all of whom had grown up with the feeling of a central stringer under their feet. Could customers make the adjustment? It was a risk.

Unlike with Haydenshapes boards, with the FiberFlex technology I started my marketing from the top end. Tom was helpful in organically sharing his enthusiasm of my creation with other elite surfers. When he talked about the benefits of FiberFlex, they listened. As the first person to ride FiberFlex, with 40 years behind him of growing up with traditional boards with straight rockers and centre stringers and winning world titles on them, he was the perfect poster boy for the openness to new ideas that I was seeking from surfers.

For my part, I found it simple to explain, but harder to sell. FiberFlex shifted the flex from the centre to the rail, which gave you that rapid spring back and acceleration. Even though the board was super-light, there was something in the carbon frame that changed the usual light feeling of EPS foam when moving through a turn. It was better and I knew it. I would always come back to, “You should go surf it yourself. You’ll then understand why FiberFlex is better, you will feel the flex.” With that thought process, I also found my tagline for the tech: “Feel The Flex.”

By instinct and from what I’d seen in the industry, I sensed that it was a good idea to start at the top: aim at the professional surfers on the World Championship Tour. Dayyan Neve was the first to adopt it. A local from Manly on Sydney’s northern beaches, Dayyan was obviously a great surfer, but also an open-minded free spirit. I went to the Bells Beach WCT contest down in Victoria with Nick Carroll, who, like Tom, had encouraged me all the way. In the car park at Bells, Dayyan rolled up. He’s a very jovial, sociable guy, and when he saw one of the boards I’d made and brought with me, he grabbed it and flexed it in his hands.

‘Man, this is amazing! I’m going to surf it in my heat right now!’

‘Really?’ I said. I was too stunned to say any more.

My hesitation must have brought Dayyan back to reality, so he didn’t surf it. He came in after his heat and said, ‘If I’d ridden your board, I’d have won!’

He took it out at Johanna Beach later, and came in saying it was one of the best boards he’d ever ridden. He fell off the WCT that year, but requalified on the World Qualifying Series riding that same board. He kept it for three and a half years, surfed amazingly on it in front of the world’s best surfers and the biggest audience in the sport, and it stayed in near-perfect condition. As one of nature’s enthusiasts, Dayyan influenced a lot of other elite surfers to give FiberFlex a try. Soon, through Dayyan’s example and advocacy, top surfers like Mark Matthews, Dan Ross and Jarrad Howse were riding FiberFlex boards in my shapes on the WQS and sometimes the WCT. All of them were great athletes and really supportive, fun guys who added to the validation my boards had got from Craig and Laura.

In truth, however, during that phase of my business I never really got a lot of enjoyment out of the process of chasing WCT or WQS athletes, and these feelings would later shape the next decade and the direction I took for the brand. Not that I didn’t enjoy the thrill of seeing my boards in contests, but I felt an underlying nervousness that I would get caught up following the same path other shapers did. I’d seen all the major surfboard brands gain a huge presence from their visibility on the elite tours, but I could also see all of the holes in their business models. It was clear that having WCT athletes on your boards didn’t automatically translate to profitability. I wanted to follow my own vision, even if it completely went against the grain of how things were conventionally done.

As a major global surfboard brand nearly a decade after first developing FiberFlex, I’m often asked why I don’t have world tour surfers in my athlete roster. I have shaped a board or two for athletes like CJ Hobgood and Travis Logie during their more recent time on tour, but I’ve pursued nothing exclusive or serious. When I did it, my aim was more to gain design feedback from those surfers rather than it being a marketing exercise. There is no simple answer for why I haven’t gone harder after WCT relationships, but since that early three-year stint I haven’t really chased it. Although I would never assume that if I did chase them, the competitive athletes would instantly be riding my boards, I’m not exactly turning up to every contest networking or courting those types of surfers either. The Haydenshapes team list is smaller than any other brand of our size and reach, and I have focused my energies on free surfers. Admittedly, shaping the typical 5’11 shortboard, the tour/contest surfboard, on repeat really wasn’t that appealing to the designer in me.

For me it’s been more about innovation than something as specific as winning contests. Working with free surfers like Craig Anderson and Creed McTaggart meant that I had few boundaries when it came to my designs. I wasn’t a slave to the shaping bay, pumping out boards on which someone could win or maybe not, depending on their personal performance on the tour. Instead, like my team riders, I was a free agent and could constantly try new things.

Although I’ve made the conscious decision to channel my energy into other areas, like building my brand through a great product, design innovation, unique branding and a more global manufacturing and distribution strategy standpoint, it’s delivered results that I don’t think I would have achieved by chasing tour surfers alone. Haydenshapes has a leading and credible global brand position, won multiple major awards and has a best selling product worldwide – with no WCT surfer on our books. My vision for the product and the brand would be based on what consumers felt when they rode it. That meant a lot more to me than having it sell based on what was seen in competition. I wanted surfers like myself, our customers, to play the key part in our discovery and growth as well as our team add their own unique voice to the brand. If I could achieve this and have a solid foundation of the business that was based on our own core strengths in design, than it would set us up for the future. It was logical. Who knows…. Maybe the WSL (formally the WCT) part of the Haydenshapes journey is still to come? Timing is everything.

Having manufactured the early FiberFlex boards and while I was gaining more confidence and validation through the feedback from professional athletes, I had been plotting how to sell it to retailers. I had my key point of difference now, and there was nothing else like it in the market. This board worked for professionals, and from my own feedback I knew it worked for everyday surfers too. A board with a wooden stringer down the centre has a really defined flex and feeling. With Fibreflex, we had broadened out the sweet spot and electrified it. It was more forgiving as it generated speed easier. Some surfers aren’t ready to let go of that “familiar” feeling, but for a new kid who learns to surf on a Fiberflex board, this is the new normal. It’s like growing up using a big tennis racquet. It’s doing what the player wants and quickly becomes what they’re used to.

To bring FiberFlex to market – which I did before approaching Dayyan and the other professional athletes – I had compiled a checklist of what it had to have. Performance was first and foremost. Then it had to be customisable. Third, a commercial model had to be as lightweight as a team rider’s board yet also be at least as durable as a polyurethane board.

A standard weight lamination had two layers of 4-ounce fibreglass on the deck and one on the bottom. A team rider’s board had half of that on the deck. I wanted the light weight of a professional rider’s board, with the durability of a board that an everyday surfer is going to want to keep using for years. And finally, I knew how much flex we wanted. If it didn’t tick all those boxes, I wasn’t going to commercialise it. But by this stage I figured I had got them all.

Now, the big question. What was it worth? I researched how much other boards with parabolic stringers were priced at. Firewire, with their wooden parabolic frames, were at a premium price of $900. This was my chance to say, I’m not a $550 or $600 board, I’m going to be an $895 board. That made mine one of the most expensive shortboards in the marketplace, which was incredibly bold. But if a customer didn’t want the $895 carbon-fibre version, I could downsell them to a non-FiberFlex board which would now be priced at $750. I did feel that my boards were worth that much at least, but needed the special difference that FiberFlex gave my brand. I had been waiting for the confidence to stand up and say, ‘My boards are some of the best in the world.’ I made the decision and implemented it in one day. One moment Haydenshapes boards were priced at $595, and the next minute the rules had changed. And amazingly, the reaction was great. Retailers and consumers cottoned on. They had seen Dayyan and the others, they’d heard what Tom had said. FiberFlex was worth it.

It was almost a shock to me when the retailers and consumers supported me and my sales took off. With a certain shyness, I had been hovering around the back, with my boards priced $150 below the premium brands. FiberFlex changed all that. I could now say to retailers, ‘My boards are different and better and this is why. It’s not just the shape, it’s the technology that is different from any other shaper’s.’ The visual side, with the black rails and white centre, was part of that point of difference. That was the catalyst for our next big step.

*